How a 14th-century English monk can improve your decision making

"File:William of Ockham.png" by self-created (Moscarlop) is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Nearly everyone has been in a situation that required us to form a hypothesis or draw a conclusion to make a decision with limited information. This kind of decision-making crops up in all aspects of life, from personal relationships to business. However, there is one cognitive trap that we can easily fall into from time to time. We tend to overcomplicate reasoning when it’s not necessary.

I've seen this happen many times in business settings. We've all been trained never to walk into the boss's office without a stack of data to support our recommendations. It's why kids make up elaborate stories when asked how the peanut butter got in the game console. It's often why we feel the need to present multiple outlier scenarios on a SWOT analysis just to prove we've done the legwork. However, this type of cognitive swirl adds time in meetings, creates inefficiencies, and can be just plain distracting.

We all do this, including me. Scratch that. Especially me. As a professional risk manager, it’s my job to draw conclusions, often from sparse, incomplete, or inconclusive data. I have to constantly work to ensure my analyses are realistic, focusing on probable outcomes and not every conceivable possibility. It’s a natural human tendency to overcomplicate reasoning, padding our thoughts and conclusions with unlikely explanations.

Recognizing and controlling this tendency can significantly improve our ability to analyze data and form hypotheses, leading to better decisions.

You may be wondering - what does this have to do with a 14th-century monk?

Enter William of Ockham

William of Ockham was a 14th-century English monk, philosopher, and theologian most famous for his contributions to the concept of efficient reasoning. He believed that when observing the world around us, collecting empirical data, and forming hypotheses, we should do it in the most efficient manner possible. In short, if you are trying to explain something, avoid superfluous reasons and wild assumptions.

Later philosophers took William’s tools of rational thought and named them Ockham’s Razor. You've likely heard this term in business settings and it is often interpreted to mean, "The simplest answer is likely the correct answer." This interpretation misses the fact that Ockham was more interested in the process of decision-making than the decision itself.

In the philosophical context, a razor is a principle that allows a person to eliminate unlikely explanations when thinking through a problem. Razors are tools of rational thought that allow us to shave off (hence, “razor”) unlikely explanations. Razors help us get closer to a valid answer.

The essence of Ockham’s Razor is this:

pluralitas non est ponenda sine necessitate, or

plurality should not be posited without necessity

Don’t make more assumptions than necessary. If you have a limited amount of data with two or more hypotheses, you should favor the hypothesis that uses the least amount of assumptions.

Three Examples

Example #1: Nail in my tire

Images: Left; NASA | Right: Craig Dugas; CC BY-SA 2.0

Observation: I walked to my car this morning, and one of my tires was flat. I bent down to look at the tire and saw a huge rusty nail sticking out. How did this happen?

Hypothesis #1: Space junk crashed down in the middle of the night, knocking up debris from a nearby construction site. The crash blasted nails everywhere, landing in a road. I must have run over a nail. The nail punctured the tire, causing a leak, leading to a flat tire.

Hypothesis #2: I ran over a nail in the road. The nail punctured the tire, causing a leak. The leak led to a flat tire.

It’s a silly example, but people make these kinds of arguments all the time. Notice that both hypotheses arrive at the same conclusion: running over a nail in the road caused the flat. In the absence of any other data about space junk or construction sites, applying Ockham’s Razor tells us we should pick the hypothesis that makes the least amount of assumptions. Hypothesis #1 adds three more assumptions to the conclusion than Hypothesis #2, without evidence. Without any more information, take the shortest path to the conclusion.

Here’s another one. It’s just as outlandish as the previous example, but unfortunately, people believe this.

Example #2: Government surveillance

"Cell tower" by Ervins Strauhmanis is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Observation: The US government performs electronic surveillance on its citizens.

Hypothesis #1: In partnership with private companies, the US government developed secret technology to create nanoparticles that have 5G transmitters. No one can see or detect these nanoparticles because they’re so secret and so high-tech. The government needs a delivery system, so the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent vaccines are just false flags to deliver these nanoparticles, allowing the government to create a massive 5G network, enabling surveillance.

Hypothesis #2: Nearly all of us have a “tracking device” in our possession at all times, and it already has a 5G (or 4G) chip. We primarily use it to look at cat videos and recipes. The US government can track us, without a warrant, at any time they want. They’ve had this capability for decades.

Both hypotheses end in the same place. Absent any empirical data, which one makes fewer assumptions? Which one takes fewer leaps of faith to arrive at a conclusion?

One more, from the cybersecurity field:

Example 3: What’s the primary cause of data breaches?

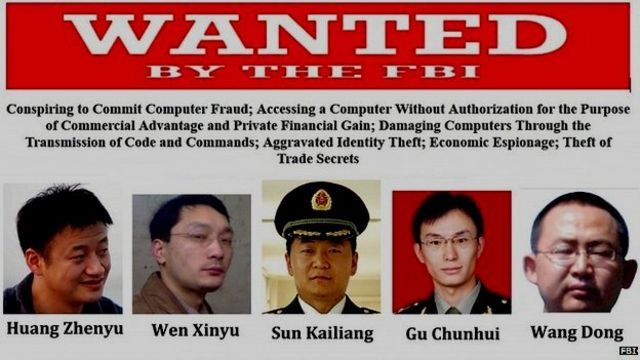

FBI Wanted Poster | Source: fbi.gov

Observation: We know data breaches happen to companies, and we need to reflect this event on our company’s risk register. Which data breach scenario belongs on our risk register?

Hypothesis #1: A malicious hacker or cybercriminal can exploit a system vulnerability, causing a data breach.

Hypothesis #2: PLA Unit 61398 (Chinese Army cyber warfare group) can develop and deploy a zero-day vulnerability to exfiltrate data from our systems, causing a data breach.

Never mind the obvious conjunction fallacy; absent any data that points us to #2 as probable, #1 makes fewer assumptions.

Integrating Ockham’s Razor into your decision making

Ockham’s Razor is an excellent mental tool to help us reduce errors and shave down unnecessary steps when forming hypotheses and drawing conclusions. It can also be a useful reminder to help us avoid the pitfalls of cognitive bias and other factors that might cloud our judgment, including fear or shame.

Here’s how to use it. When a conclusion or hypothesis must be drawn, use all available data but nothing more. Don’t make additional deductions. Channel your 10th-grade gym teacher when he used to tell you what “assumptions” do.

You can apply Ockham’s Razor in all problems where data is limited, and a conclusion must be drawn. Some common examples are: explaining natural phenomena, risk analysis, risk registers, after-action reports, post-mortem analysis, and financial forecasts. Can you imagine the negative impacts that superfluous assumption-making could have in these scenarios?

Closely examine your conclusions and analysis. Cut out the fluff and excess. Examine the data and form hypotheses that fit, but no more (and no less - don’t make it simpler than it needs to be). Just being aware of this tool can reduce cognitive bias when making decisions.